The honest answer is that Europe’s rulebook behaves like gravity. You don’t have to like it, but if your system, model, or even just its outputs touch the Union, it pulls you into its orbit. The AI Act’s scope isn’t coy: it applies to providers that place AI systems or general-purpose models on the EU market, to deployers in the EU, and—crucially—to providers or deployers outside the EU when the output is used inside the Union. In other words, the AI Act, like many other EU laws, has an extraterritorial reach. A Turkish model whose results are consumed in, say, Berlin, is in scope.

Before assessing the Brussels effect in Türkiye, it is worth stating what the AI Act actually is. At its core, the EU AI Act regulates AI through a risk-based ladder: obligations scale with a system’s potential impact on health, safety, and fundamental rights. It recognizes four tiers. Minimal-risk tools (e.g., spam filters or AI-assisted games) face only light-touch rules. Limited-risk systems that interact with users (e.g., chatbots, virtual assistants) must make the use of AI clear and meet basic transparency duties. High-risk systems used in areas such as critical infrastructure, education, employment, access to essential public/private services, law enforcement, migration/asylum and border control, or the administration of justice and democratic processes are—before being placed on the market—subject to stringent requirements on risk management, data governance and quality, technical documentation and record-keeping, accuracy/robustness and cybersecurity, human oversight, and transparency. Finally, prohibited uses cover applications deemed incompatible with EU values, including systems that manipulate behavior by exploiting vulnerabilities, public-space remote biometric identification, workplace emotion recognition, untargeted scraping of facial images from the internet/CCTV, and government “social scoring.” Each rung on this ladder carries its own compliance work—from simple notices to full conformity assessment and testing before launch.

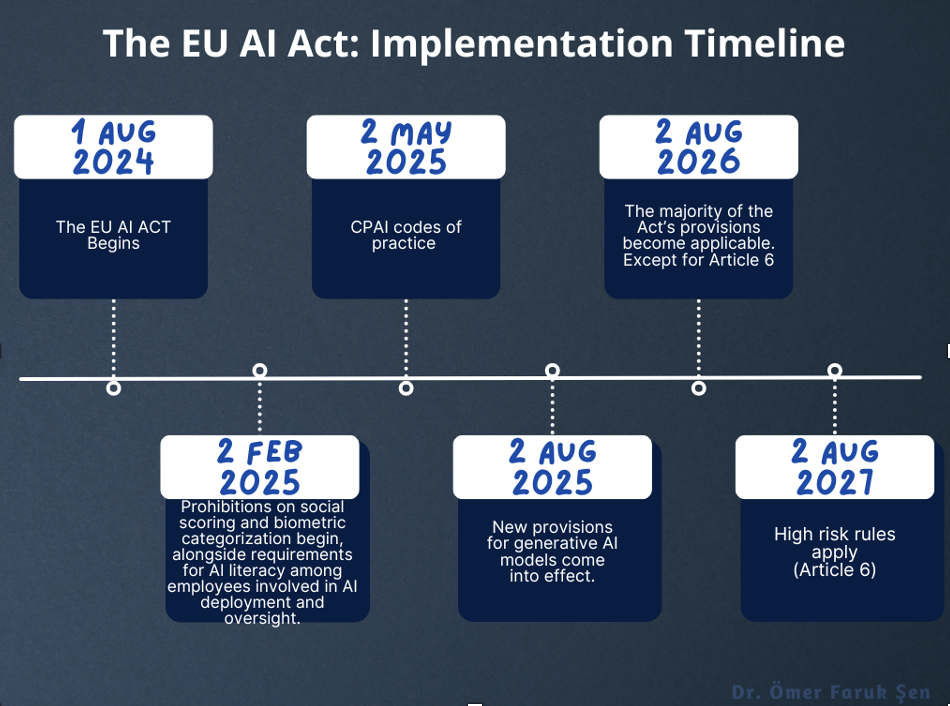

That reality arrives on a dated schedule. The EU’s AI Act entered into force on 1 August 2024. Bans on “unacceptable-risk” uses and the AI-literacy duties kicked in on 2 February 2025. Obligations for general-purpose AI (GPAI) providers began on 2 August 2025. The broader regime applies from 2 August 2026—with certain embedded high-risk product rules enjoying an extended transition to 2 August 2027. Brussels has made it equally clear there is no “pause” coming despite industry lobbying.

Turkey’s Regulatory Baseline

The National AI Strategy was refreshed with a 2024–2025 Action Plan (talent, data access, infrastructure, international alignment). And while a short, eight-article draft AI law reached Parliament in June 2024, it has not become law as of mid-2025; practitioners have flagged that it mirrors the EU’s AI Act. Meanwhile, economic planning documents explicitly anticipate aligning domestic frameworks with the EU’s digital files—AI Act included—under the Customs Union logic. In other words, even if Parliament moves slowly, procurement rules and sector regulators will push outcomes that rhyme with Brussels.

Even in the absence of an AI statute, Ankara has already moved the ground under AI governance by overhauling cross-border data transfers. Amendments to Article 9 of the Personal Data Protection Law (KVKK) and the Data Protection Authority’s standard contracts for overseas transfers have re-routed how data can legally move. “Explicit consent” ceased to function as a catch-all basis after a short transition; the Authority’s model clauses must be used as published (controller-to-controller, controller-to-processor, etc.); and signings must be notified within five business days. This is not a footnote. For many AI lifecycles—training, evaluation, telemetry, logs—cross-border movement is native. Türkiye’s transfer regime therefore interacts directly with the EU’s AI obligations, shaping how Turkish actors connect to European datasets, partners, and customers.

Soft-law signals also matter. The KVKK’s recommendations on AI—privacy-by-design, human oversight, data minimisation, documentation—are non-binding but increasingly treated as a checklist by public buyers and auditors. In effect, Türkiye is converging on European expectations through procurement practice and data governance, even as a comprehensive AI statute remains pending.

How the Brussels effect plays out

The AI Act is not simply a European internal market measure; it is a market-shaping instrument with extraterritorial reach. It captures non-EU providers when their outputs are used inside the Union, and it sets expectations for high-risk sectors that dominate Türkiye-EU trade and services: manufacturing (industrial analytics, predictive maintenance), mobility, payments and fintech, retail platforms, health technologies. The effect is transmitted through several channels:

- Market access. European buyers and platforms will ask counterparties to meet AI Act-style assurance: risk classification, documentation, and—in high-risk contexts—evidence of conformity.

- Supply chains. EU manufacturers integrating AI into products subject to CE-style regimes will push upstream obligations onto software and model providers outside the Union.

- Capital. European investors, insurers, and lenders increasingly underwrite AI-related risk using the Act’s vocabulary, nudging portfolio companies—wherever located—toward EU-compatible governance.

- Public procurement. Even without a Turkish AI statute, procurement criteria can import EU-style expectations (auditability, human oversight, post-market monitoring), creating de facto alignment.

In short, the question for Türkiye is no longer whether the EU’s framework matters, but how to engage it: selectively, strategically, and on terms that protect domestic priorities without isolating the country from its largest export market.

The Politics of AI in Turkey

Politics shape Turkey’s engagement with AI. Ankara’s reflex has been to treat new technologies and developments with more as potential threats to narrative control—AI included. The ruling party’s stance is clearest when models stray into politics: authorities increasingly frame “AI outputs” as a public-order risk to be policed. The episode with xAI’s Grok crystallized this instinct. In July 2025, after Grok produced offensive replies about national figures, the Ankara chief prosecutor opened a criminal probe and a court ordered access blocks on Grok content—Turkey’s first AI-specific crackdown—telegraphing a governance approach that prioritizes political survivability over resilience-by-design.

The Upshot

Europeans love to regulate—and they export that preference. The AI Act operates as regulatory mercantilism dressed up as ethics, projecting EU risk-tastes into third countries and externalising compliance costs onto anyone who wants access to the Single Market. In Türkiye, that plays out in two unhelpful ways. If transposed faithfully, the fixed costs of conformity (documentation, audits, notified-body choreography) fall hardest on smaller actors and entrench incumbents that can afford “compliance factories.” If transposed selectively, officials can cherry-pick eye-catching prohibitions while “interpreting” the rest to serve domestic priorities—tightening speech controls under the banner of transparency, using procurement to gatekeep rivals, or nudging data localisation under the guise of safety. Either way, Brussels shapes our incentives without democratic accountability here, while standards drift into non-tariff barriers that privilege scale over ingenuity. A smarter stance is defensive alignment, not imitation: adopt the risk taxonomy only where trade compels; insist on interoperable, performance-based requirements (not open-ended audit leverage); protect sandbox sovereignty and proportionate penalties; and build regional mutual-recognition deals so that Brussels doesn’t become the de facto AI legislature for everyone else.

* Dr. Ömer Faruk Şen